childish objects \ systems of belief / Undo. Unravel. Go back, and further back, still. Go home. (Are you my Mother?) for Boty Goodwin 1936 and 2013

performance document – 4 passports

childish objects \ systems of belief / Undo. Unravel. Go back, and further back, still. Go home. (Are you my Mother?) for Boty Goodwin 1936 and 2013

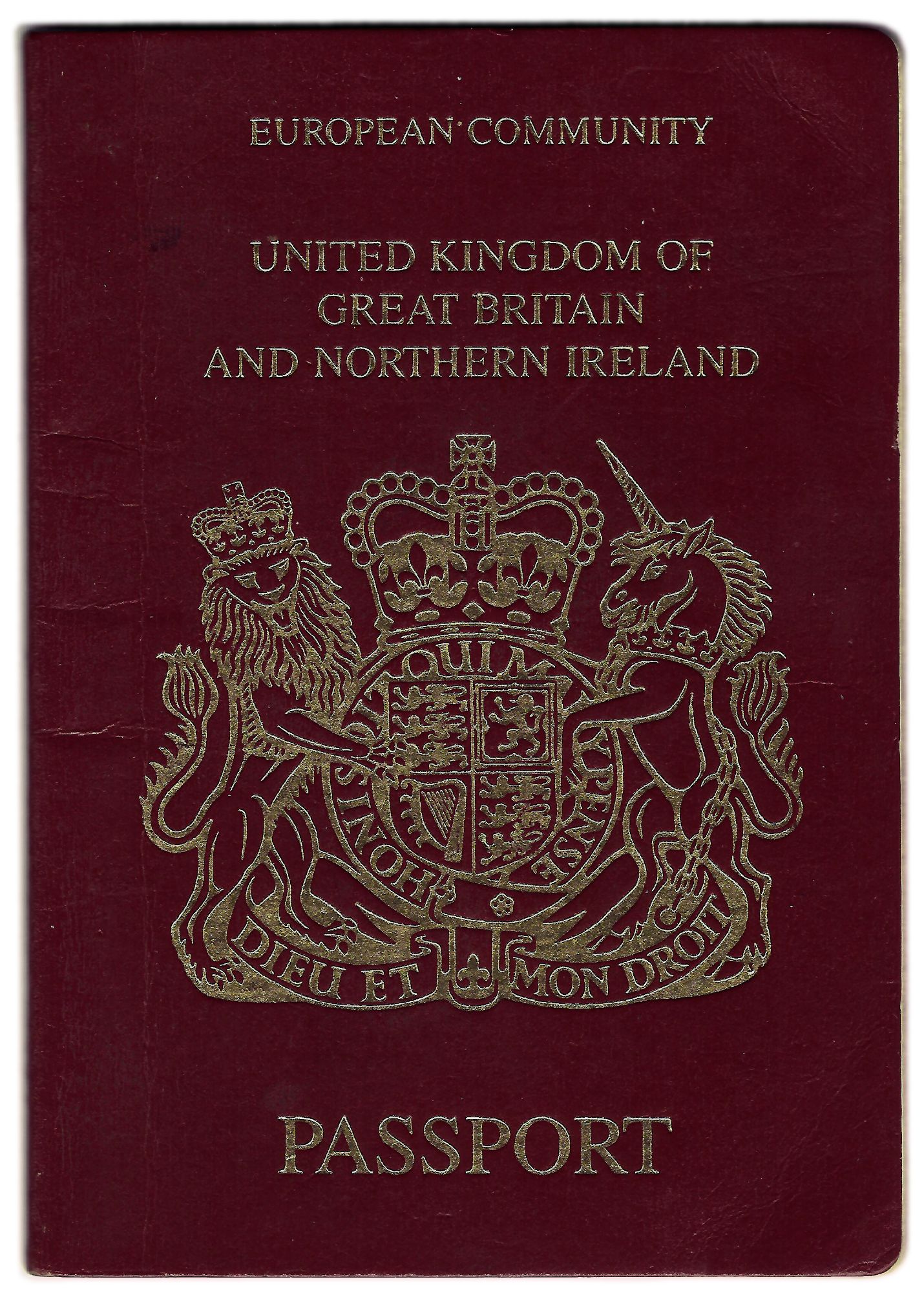

performance document – 1 of 4 passports

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland Passport: Boty Goodwin, British Citizen 09 SEP 94 - 09 SEP 04 014301698 (relic)

childish objects \ systems of belief / Undo. Unravel. Go back, and further back, still. Go home. (Are you my Mother?) for Boty Goodwin 1936 and 2013

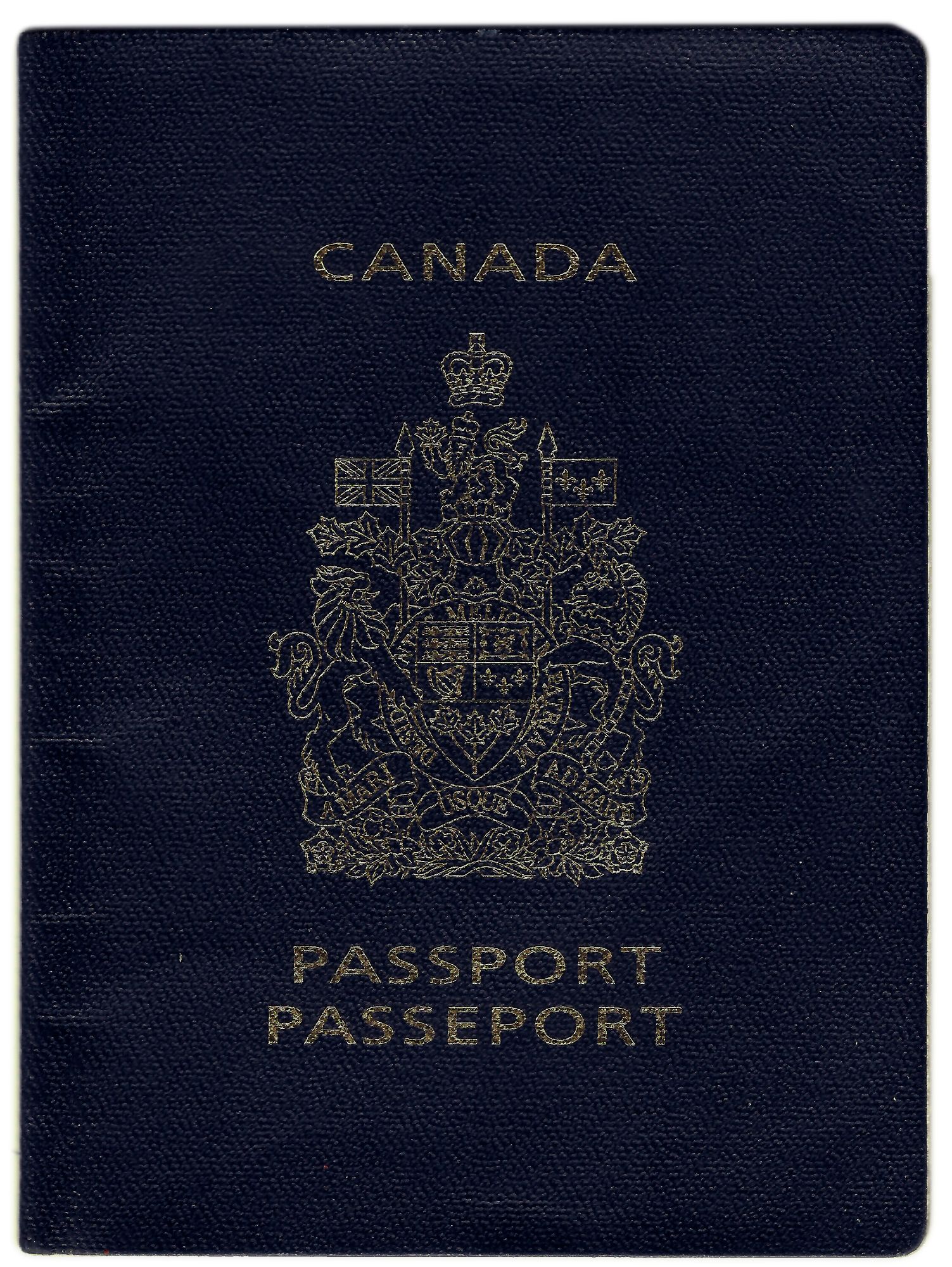

performance document – 1 of 4 passports

Canada Passport Passeport: Nichola K. Feldman-Kiss Nationality / Nationalité CANADIAN / CANADIENNE 31 DEC \ DÉC 09 - 31 DEC \ DÉC 14 WN291330

childish objects \ systems of belief / Undo. Unravel. Go back, and further back, still. Go home. (Are you my Mother?) for Boty Goodwin 1936 and 2013

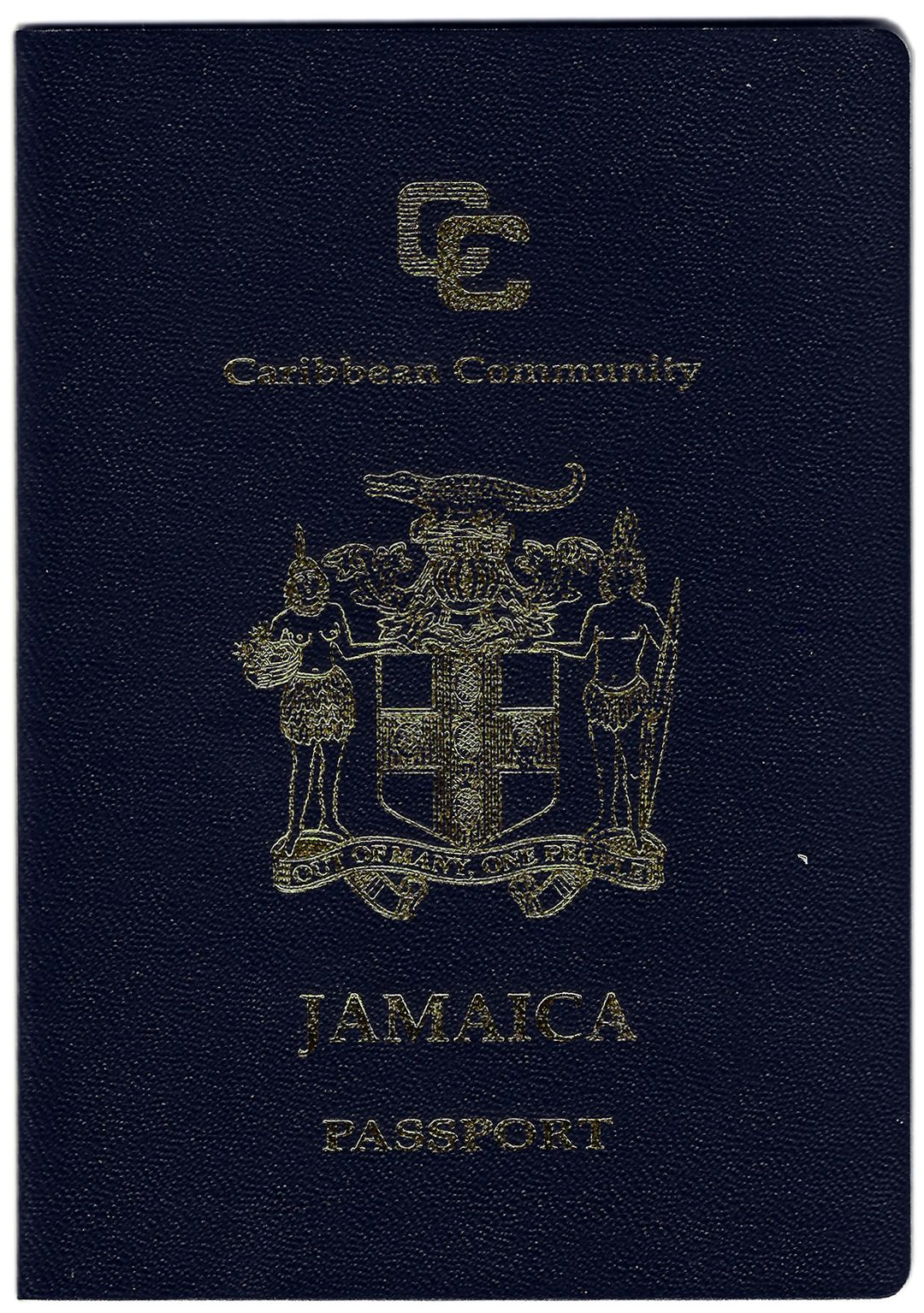

performance document – 1 of 4 passports

Europäishe Union Bundesrepublik Deutschland Reisepass: Nichola K. Feldman-Kiss Saatsangehörigkeit Deutsch 12.01.2011-11.01.2021 C4F7X00VZ

childish objects \ systems of belief / Undo. Unravel. Go back, and further back, still. Go home. (Are you my Mother?) for Boty Goodwin 1936 and 2013

performance document – 1 of 4 passports

Caribbean Community Jamaica Passport: Nichola K. Feldman-Kiss Visual Artist Nationality Jamaican 07 MAY 2013 - 06 MAY 2023 A343379

childish objects \ Undo. Unravel. Go back, and further back still. Go home. (Are you my Mother?) for Boty Goodwin 1936 – 2013

performance document – identity documents: European Community United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland Passport (expired); Canada Passport; Europäische Union Bundesrepublik Deutschland Reisepass; Caribbean Community Jamaica Passport.

In a performative act examining migration, multiplicity and complex identity, alongside equally complex emotional states of home, (non)belonging, forgiveness and ethical responsibility to global citizenship, I have become tri-citizen –Canada, Germany and Jamaica. This exceptional and accidental privilege of birth and times is a great motivator of my work.

In 1936 my father’s German family of Lutheran mother and Jewish father, elder daughter and younger son left the Nazi occupation marking the beginning of a long trek out of Europe. The little family’s flight from home was precipitated by Rassenschande –miscegenation policies set in motion by the 1935 Nuremberg Laws which criminalized their love blind to faith boundaries. London 1941, the stateless father was granted British subjecthood to facilitate passage to the colonies. The family boarded an unnamed Dutch merchant ship to journey in convoy across the Atlantic to Halifax. The rejected vessel continued on to (then British) Guyana where the family boarded the Canadian steamship, Lady Drake, destined to the Barbados tropical paradise. They disembarked the steamship December 6, 1941, the day before the attack on Pearl Harbor. The parents never again spoke of war nor passed their German language to their children. Subsequent to the family’s safe arrival the Lady Drake was torpedoed by a German Uboat off the coast of Bermuda.

In 1957 my Bajan father and Jamaican mother arrived in Canada, both British subjects. In 1962, the year of my birth, Jamaica became independent of colonial rule. My parents became citizens of Canada. A child of indigenous islanders, colonials of the sugar industry, folks stolen from western Africa made slaves and merchant marines of southern Portugal, my Jamaican mother had not held a legal Jamaican identity.

In 1999 reformations to German citizenship law, granted entitlement to those who had lost their German identities either through revocation or flight from Nazi party persecution. The lost citizens were invited to repatriate and their descendants invited to participate in German society by way of naturalization. In 2000, I submitted to a lengthy process of ancestral document retrieval to prove my linage. I contextualized my negotiation of the German bureaucracy as a performance of entitlement and forgiveness. In 2010, I became a naturalized citizen of Germany. In 2011, I was granted my first German passport. I first used this passport in transit to Sudan to research displacement and trauma associated with the colonial project.

In 2008, I initiated an application for Jamaica citizenship by descent. In 2012, I became a Jamaican citizen. In 2013, I was granted my first Jamaica passport. I continue to research colonialisms, imperialist practices, traumatic memory and self-determination.

Today, 1 November 2021, the UNHCR recognizes 26.4 million people in flight –seeking refuge outside of their countries of origin (who bear legal responsibility for inclusion of nationals within the international nation state system of laws and recognitions). A further 4.2 million people are recognized to live in statelessness. About half of the people who embody these statistics are children. To be stateless is to exist outside of international human rights frameworks. The place of statelessness is the ultimate state of exception.

“The relation of exception is a relation of ban. He who has been banned is not, in fact, simply set outside the law and made indifferent to it but rather abandoned by it, that is, exposed and threatened on the threshold in which life and law, outside and inside, become indistinguishable. It is literally not possible to say whether the one who has been banned is outside or inside the juridical order.”

Giorgio Agamben Homer Sacer 2013

I am indebted to Boty Goodwin who lived 1966 to 1996. Following her death, I came into possession of her Jeep Cherokee. The British passport in this artwork belonged to her. I found it in her car. How I came to own the car is its own strange story. The representation of British subjecthood was a necessary piece in the retelling of my parent’s journey. Boty’s own tragic story both inspired and completed this search for belonging.